Black grouse diet and behaviour

Black grouse diet

Adult black grouse are herbivorous and feed

opportunistically but selectively on a variety of food items.

Females require a protein and energy-rich food source in the

pre-laying period in spring, and utilise the inflorescences of

cotton grass Eriophorum spp., buds of larch Larix spp., alder Alnus spp., birch Betula

spp., and leaves, buds and flowers of ericaceous shrubs and

herbs such as Ranunculus spp. (flowers in buttercup family) and marsh marigolds Caltha palustris.

Adult black grouse are herbivorous and feed

opportunistically but selectively on a variety of food items.

Females require a protein and energy-rich food source in the

pre-laying period in spring, and utilise the inflorescences of

cotton grass Eriophorum spp., buds of larch Larix spp., alder Alnus spp., birch Betula

spp., and leaves, buds and flowers of ericaceous shrubs and

herbs such as Ranunculus spp. (flowers in buttercup family) and marsh marigolds Caltha palustris.

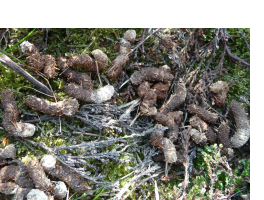

In winter, black grouse feed on shrubs such as Vaccinium spp., heather Calluna spp. and juniper Juniperus. If these are snow-covered, they can rely on catkins, buds, twigs and needles of various tree species, especially birch, alder , rowan and willow, but also spruce and pine.

In contrast to adults, black grouse chicks eat invertebrates (mainly insects )

for the first two to three weeks of life. Thoughout this time, the amount of insects in the diet declines and by 3-4 weeks is <20% of diet (Wegge & Kastdalan 2008). Most of the diet consists of insect larvae such as butteflies, moths, sawflys and ants (Wegge & Kastdalan 2008). he timing of grouse hatching matches the temporal abundance of insect food items (Baines et al. 1996; Wegge et al. 2010). After shifting a plant-based diet, grouse chicks eat a range of species, particulalrly bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and bog bilberry (V. uliginosum). Other important species include cranberry(Oxycoccos quadripetalus) and small cow-wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum). Chick diet includes leaves, berries, seeds and flowers.

In contrast to adults, black grouse chicks eat invertebrates (mainly insects )

for the first two to three weeks of life. Thoughout this time, the amount of insects in the diet declines and by 3-4 weeks is <20% of diet (Wegge & Kastdalan 2008). Most of the diet consists of insect larvae such as butteflies, moths, sawflys and ants (Wegge & Kastdalan 2008). he timing of grouse hatching matches the temporal abundance of insect food items (Baines et al. 1996; Wegge et al. 2010). After shifting a plant-based diet, grouse chicks eat a range of species, particulalrly bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and bog bilberry (V. uliginosum). Other important species include cranberry(Oxycoccos quadripetalus) and small cow-wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum). Chick diet includes leaves, berries, seeds and flowers.

Grouse behaviour: outside the lekking season

Grouse can show a number of behaviours outside the commonly observed lekking. Many of these behaviours are adaptations to the environment in which grouse live, including the extreme cold and the risk of predation. Two of the most important behaviours in relation to these are snow burrowing and the formation of mixed-sex flocks. Both are winter behavhiours.

Snow holes

In northern climates, thermoregulation during winter when temperatures may dip below -40°C are a signficant problem. One adaptation to this is snow burrowing. Snow burrows are formed when the grouse digs into the snow layer. Despite being entirely closed, the roof is thin enough to prevent carbon dioxide buildup (Korhonen 1980). The temperature in the burrow is around -5 to 0°C and this means a significant saving in energy for the grouse in comparision to outside temperatures (Marjaknagas et al. 1984).

In northern climates, thermoregulation during winter when temperatures may dip below -40°C are a signficant problem. One adaptation to this is snow burrowing. Snow burrows are formed when the grouse digs into the snow layer. Despite being entirely closed, the roof is thin enough to prevent carbon dioxide buildup (Korhonen 1980). The temperature in the burrow is around -5 to 0°C and this means a significant saving in energy for the grouse in comparision to outside temperatures (Marjaknagas et al. 1984).

Snow burrowing is seen as very important for grouse, especially during very cold periods. As a result, snow conditions play an important role in their winter ecology. If the snow is not thick enough, or has a hard crust, grouse are unable to burrow and this can lead to higher energetic demands and increased overwinter mortality.

Winter flocks

During the early winter period to spring (November to April), black grouse of both sexes gather together in mixed-sex winter flocks to roost and forage together. The composition and stability of these flocks can vary through the winter and at times may become single-sex (Koskimies 1957; Robel 1969; Ciach et al. 2010). Winter flocks probably play an important role in avoiding or diluting predation risk e.g. goshawks Accipiter gentilis (Widén 1987). Males start to leave the flocks in spring to take up places on the lek.

References

Baines, D., Wilson, I.A. & Beeley, G. (1996) Timing of breeding in black grouse Tetrao tetrix and capercaillie Tetrao urogallus and distribution of insect food for the chicks. Ibis, 138, 181–187.

Ciach, M., Wikar, D., Bylicka, M. & Bylicka, M. (2010) Flocking behavior and sexual segregation in black grouse Tetrao tetrix during the non-breeding period. Zoological Studies, 49, 453-460.

Korhonen, K. (1980) Microclimate in the snow burrows of willow Grouse (Lagopus lagopus). Annales Zoolgi Fennici, 17, 5–10.

Koskimies, J. (1957) Flocking behaviour in capercaillie, Tetrao urogallus (L.), and blackgame, Lyrurus tetrix (L.). Finnish Game Research, 18, 1-32.

Marjakangas, A., Rintamäki, H. & Hissa, R. (1984) Thermal responses in the capercaillie Tetrao urogallus and the black grouse Lyrurus tetrix roosting in the snow. Physiological Zoology, 57, 99–104.

Robel, R.J. (1969) Movements and flock stratification within a population of blackcocks in Scotland. Journal of Animal Ecology, 38, 755-763.

Wegge, P. & Kastdalen, L. (2008) Habitat and diet of young grouse broods: resource partitioning between Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) and Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) in boreal forests. Journal of Ornithology, 149, 237-44.

Wegge, P., Vesterås, T. & Rolstad, J. (2010) Does timing of breeding and subsequent hatching in boreal forest grouse match the phenology of insect food for chicks? Annales Zoologica Fennici, 47, 251–260.

Widén, P. (1987) Goshawk predation during winter, spring and summer in a boreal forest area of central Sweden. Holarctic Ecology, 10, 104–109.